By Agnieszka Gautier

When Curtis Rattray walks on Tahltan land, he often pauses to write in a tattered notepad. He jots down descriptions of the land, observations of wildlife, and sometimes water quality measurements at creeks and rivers. But mainly, he reflects on the essence of the place. “Most Indigenous people sense the spirit and personality of a place,” said Rattray, who co-founded and leads the Tu’dese’cho Wholistic Indigenous Leadership Development (TWILD), the first Tahltan non-governmental organization. “Each place has a spirit like you and I, and we name those places based on the essence of that place.”

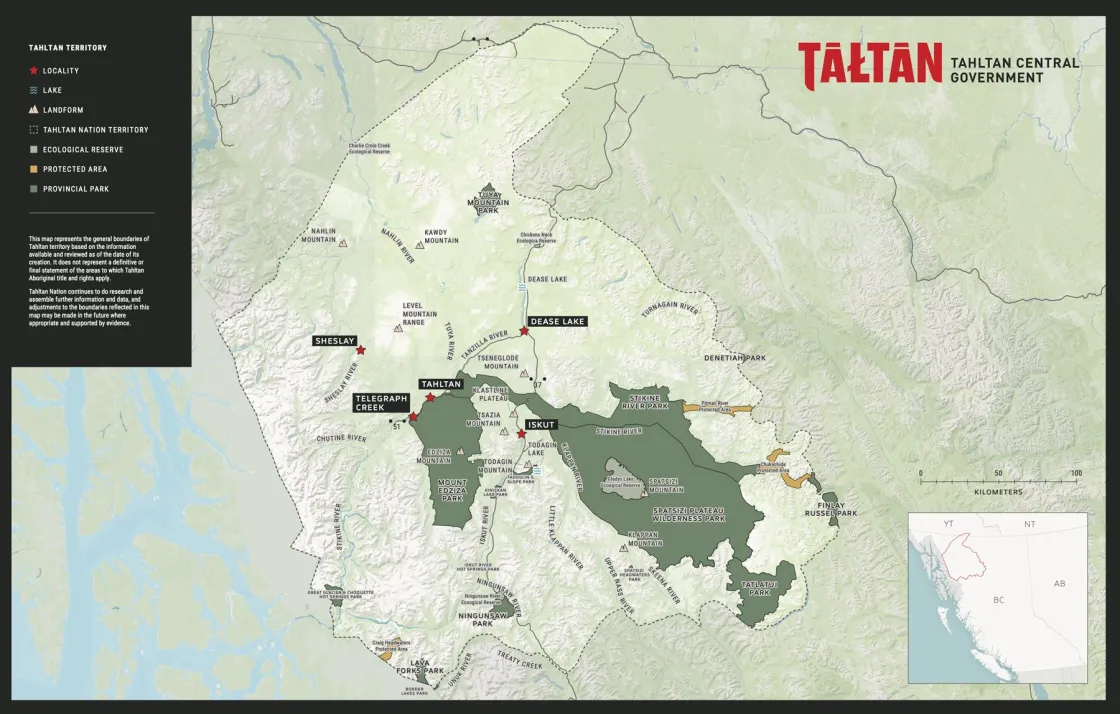

The Tahltan Territory is a mountainous region about the size of the US state of Indiana or Portugal, covering about 11 percent of the remote northwestern portion of British Columbia, Canada. Huddled between the Cassiar Mountain range to the east and the Alaska Boundary Range to the west, a valley unfolds where the Stikine, Nass, and Skeena Rivers flow. The Tahltan people make up over three-quarters of the residents in Tahltan territory, dispersed between Telegraph Creek, Iskut, and Dease Lake, where Rattray lives. While the maps of the territory may include names in English, these locations also have different names that resonate with generations of Tahltan people. These specific areas of historical and cultural significance, known as “placenames,” are gateways to ancient stories for the Tahltan.

Over several years, Rattray drafted a map with his grandmother, Elizabeth Edzerza, marking placenames he encountered in his travels to fish camps and through conversations with her and other Elders. With the support of TWILD, Rattray created a digital version of the map with the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA), a program at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). The map serves as an interactive way for communities and especially youth to learn ancestral knowledge. Keyeh: Tahltan Cultural Atlas—keyeh meaning our village or community—highlights Tahltan placenames alongside historical information and Indigenous and scientific knowledge about the lands and waters of Tahltan territory. (The atlas is currently available for community members and school teachers only.)

Colonial legacies

When TWILD started, its leaders focused on taking youth out on the land, since many Tahltan youth had never seen or experienced their ancestorial land. One such youth was Lauren Clavelle, who always knew she was Tahltan, but did not experience engaging with the land until she was 18 years old. That was five years ago. A political science student at the University of Calgary, Clavelle met Rattray in the summer of 2022 at the Tahltan Central Government’s Annual General Assembly (AGA) in Dease Lake, Canada. Clavelle mentioned wanting to reconnect with her culture, so Rattray offered her a contract with TWILD, introducing her to the atlas project. He emailed her a bunch of documents, and asked if she could upload them into the database. “That’s how I started adding content to the atlas,” she said. Members of ELOKA helped train Clavelle in how to use the Nunaliit software, which is the basis for all of its community-led atlases. The technology, which ELOKA has been using since 2008, supports knowledge documentation projects across the Arctic.

Growing up, Clavelle knew little about her culture, tracing her Tahltan ancestry through her maternal grandfather who was born in Telegraph Creek, a two-day drive from her own home. Owing to this disconnection was the knowledge that her grandfather attended a Canadian residential school administered by the Baptist Church in Whitehorse, Yukon. “But outside of that, I didn’t really know anything about my culture or community,” she said. Residential schools were created to isolate Indigenous children from their own culture and language in order to assimilate them into the dominant Canadian settler culture. After spending 12 years as a year-round student at the Whitehorse Indian Mission School, Clavelle’s grandfather lost his connection to his community and land, returning to Telegraph Creek as an adult.

Residential schools have had a profound and long-lasting effect on First Nations peoples. Around 150,000 children were taken from their homes and placed into distant government-sponsored residential schools between 1883 and 1997. “That’s really why TWILD got started,” Rattray said. “We wanted to do something to address intergenerational trauma.”

In a 2010 study of the impact of residential schools, Gwen Reimer defined historical trauma as “colonial subjugation which disrupted the process of Aboriginal cultural identity formation.” She further described intergenerational trauma as the “[u]nresolved and cumulative stress and grief experienced by Aboriginal communities [that] is translated into a collective experience of cultural disruption and a collective memory of powerlessness and loss.”

In 2008, Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper publicly apologized for the residential school system, following the largest class-action lawsuit in Canadian history. This legal action led to the creation of the Trust and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). The TRC spent six years documenting witness testimony of over 6,000 survivors of the school system, culminating in a 2015 report that declared residential schools a form of cultural genocide. The report emphasized that “most significantly to the issue at hand, families [were] disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next.”

When Rattray speaks about intergenerational trauma, he is not just talking about his people. “A lot of this comes from colonization and wars of conquest,” he explains. “But my theory is that Europeans are heavily traumatized. Everybody talks about the biological diseases that were brought over to the Americans as a turning point to European conquest of the Americas, but they also brought trauma. And that’s where our intergenerational trauma started.” Being half-Scottish, Rattray draws a parallel with Scotland’s history of assimilation under English rule. “It was really similar to what is happening with Indigenous peoples in the Americas,” he said.

A path to the atlas

Rattray and ELOKA principal investigator Noor Johnson met at the Festival of Northern Fishing Traditions in Finland in 2018. After learning more about each other's work, they agreed to explore a partnership to create a digital atlas that would combine the cultural knowledge and place names Curtis was documenting with ecological and observing knowledge. Curtis was interested in using this atlas as a teaching tool for schools in Dease Lake. Work on the atlas began in 2021; Rattray and Clavelle along with another Tahltan student, Melissa van Veen, meet regularly with ELOKA staff to work on atlas design and identification of relevant content.

Developing and expanding the Tahltan cultural atlas is a collaborative process that empowers cultural identity formation, which Rattray sees as a step towards healing. For Rattray, restoring placenames in the Tahltan language reconnects Tahltan people with their land. However, placenames can vary even among Tahltan communities. For instance, what Rattray's grandmother named a location might differ from what someone from the Iskut or Telegraph Creek communities calls it, with their own unique experiences continuing to shape their relationships with the land. “It comes back down to trust.,” Rattray said. “We need to trust that people are making an honest effort with the names they’ve learned.”

Currently, the atlas features three main categories: Tahltan Placenames, Historical Events, and Ecological Events. The Tahltan Placenames holds a little over a dozen placenames, with the Tahltan Territory divided into political regions of the seven Tahltan Tribes or Houses bearing Tahltan names. When a user clicks on a placename, a short story or background information pops up, revealing a deeper meaning and significance to that location and its name. For instance, a rock bluff with a long white vertical stain is named Tsesk'iye Chō Ts'iseledzi, which translates to “Crow big pee down” or “[where] Big Raven urinated.” This is tied to the Tahltan Nation's two clans: Tsesk’iye Chō (Tses-kee-ya), or Crow, and Ch’iyōne (Chee-oanah), or Wolf. According to Tahtlan stories, the legendary bird known as Tsesk’iye Chō once flew from his house and over the river to use the rock for his bathroom. According to Rattray’s grandmother, when the Department of Highways widened Telegraph Road and blasted this rock, the head of Tsesk’iye Chō appeared. As the atlas explains, “This shows that our stories about Tsesk’iye Chō must be true and that our stories continue today.”

The Historical Events section of the atlas digs deeper into the history of colonized naming. “We’re showing how and when these names got changed and the stories behind them,” Rattray said. The names are a mix of Tahltan and Indo-European languages, displaying the history of geological surveying of Tahltan land. Meanwhile, the Ecological Events section divides the land into 11 watersheds and includes subcategories such as Observations, Ecological Knowledge, and Plant Habitats. These subcategories showcase ecological observations and community-led monitoring, including plant regeneration after wildfires.

Clavelle also spoke with Curtis’s cousin, Elder David Rattray, about such ecological changes taking place. Elder Rattray spoke of his snowshoeing experiences as a young boy to the present. “I don’t think that we get to hear enough from our Elders. There’s not enough interaction between older generations and younger,” Clavelle said. “So, for me it was just really meaningful that he was willing to take the time out of his day to make some space for me.”

Into the classroom

TWILD is deeply committed to fostering connections between Elders and youth. The organization plans to bring the atlas into classrooms for students from kindergarten through middle school. Rattray said, “We want the older kids, the grades six and seven, to interview Elders and learn new place names, so that they then add them to the Atlas.”

For Clavelle, contributing to the atlas by uploading placenames and the stories behind them has been an honor. “I’ve learned how traditional knowledge can be passed down to future generations and what that might look like in today’s context,” she said. Unlike Rattray, whose relationship with the territory started by walking it in-person, Clavelle’s relationship with the land began remotely. “Essentially, I would be given a document, and it would say Tuya Lake. It would have the story behind the name and who told that story. Then I had to go onto Google Maps to locate it and then find it on the Tahltan Atlas.” Her virtual experience was followed by an in-person experience of visiting that area. Working on the atlas provided Clavelle the opportunity to better understand her relationship with the land, developing a love and deep appreciation for her culture and homeland.

The atlas serves as a doorway into Tahltan Territory, embodying both cultural and personal reconciliation. For Rattray, walking the land and restoring Tahltan names on the map are critical acts that help reclaim Tahltan cultural power. “We need to be doing this,” he emphasized. Rattray’s Tahltan name is Nath Glani Atz, which refers to the ground after the caribou have walked on it, or caribou tracks. When Rattray walks in very remote places, as much of Tahltan Territory is, he feels a deep sense of connection to the land. “There is no scientific explanation [for this feeling]. The only explanation I can come up with is from our stories of Creation, respect, and kinship.”

Rattray hopes to instill this same sense of connection in the next generation of Tahltan youth. By bringing the atlas to the school district and combining place-based learning with digital tools, he aims to help youth reconnect with Tahltan placenames, stories, and their ancestral roots.