By Agnieszka Gautier

When Elder Earl Atchak speaks, he points his finger for emphasis, keeping rhythm like a conductor. He leans into the audience, a classroom of 10- and 11-year-olds; each word he speaks plays like a set of staccato notes. “The tundra is pure. When you go out in the tundra, you go to a place that doesn’t belong to you,” he says. “It belongs to your children.”

In Chevak, Alaska, Elders tell stories about the environment they call home because it is the backbone of their cultural traditions and identity. Patches of lakes permeate the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta region of Western Alaska, with swirling rivers, stretches of arid tundra, and no trees. To care for this environment is to care for their Cup’ik community—a group of southwest Alaskan Natives named after one of the two main dialects of the Yup’ik language.

Elder Atchak appears in several short videos made by the Chevak sixth graders. The Chevak Traditional Council, a nonprofit organization focused on preserving the Cup’ik way of life, requested that youth interview their Elders about important places for the children. The result was a series of videos that would eventually end up in the online Nunaput Atlas, which is sponsored in part by the Council, and which supports environmental and cultural observations and story sharing.

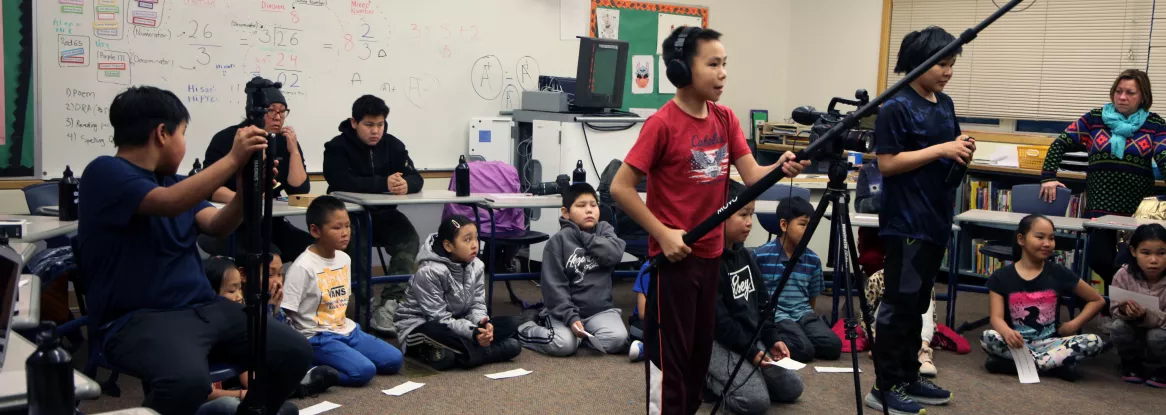

The Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA), a program at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), worked closely with the Chevak Traditional Council, along with the Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council (YRITWC) and the US Geological Survey, to create the online atlas. In November 2022, videography experts from the organization See Stories taught a classroom of Chevak sixth graders videomaking skills to make short videos for the Nunaput Atlas.

Sitting at the feet of the Elders

By creating videos that focus on meaningful places, the sixth graders dug deep to tell important stories about their lives, Chevak, and their community. By the end of an intense week of production and editing, 15 two-to-three minute videos were presented to an audience of school and community members, who erupted in cheers like a rock concert whenever images of Chevak appeared.

The videos eventually reached an even larger audience. Six short videos were chosen to enter the Alaska International Film Festival in Anchorage. Two made it for the December 2023 screening. In March 2023, all the videos were presented at the Alaska Tribal Conference on Environmental Management (ATCEM) in Anchorage. Eventually, the videos will find a permanent home on the Nunaput Atlas, marking a significant exchange in time to be archived for future generations.

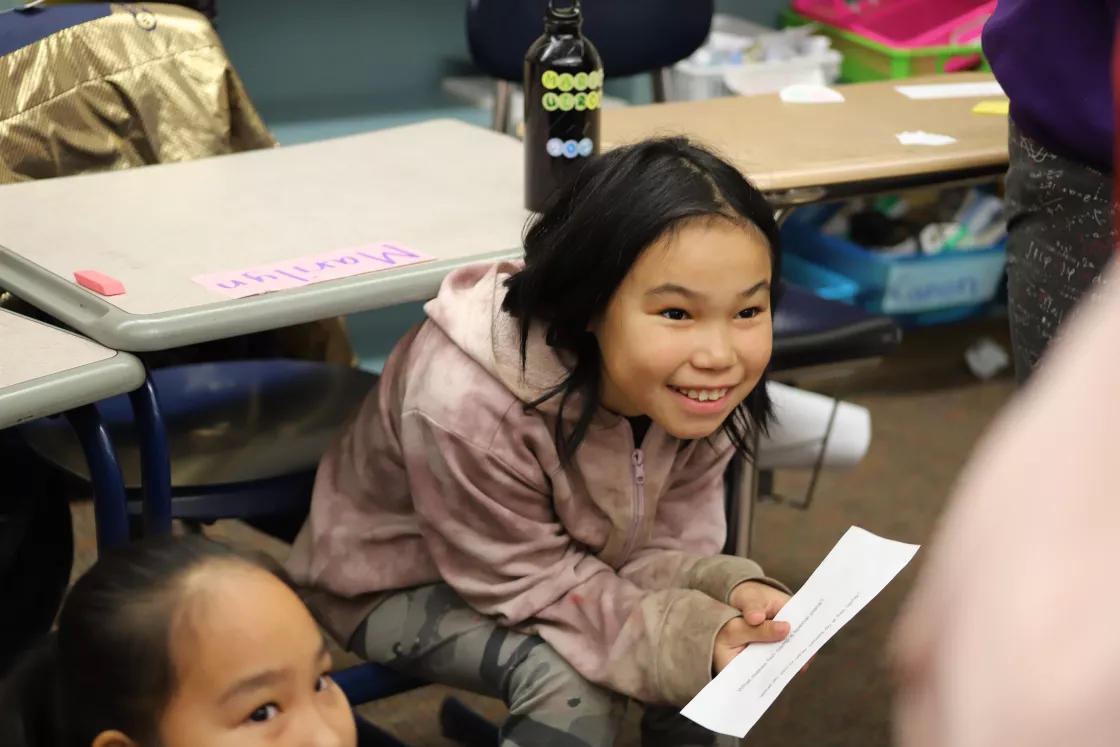

The idea of interviewing Elders started years earlier. Supported by a collaborative National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to YRITWC and ELOKA, the Chevak Traditional Council invited the nonprofit organization See Stories, which builds inclusive communities through film and story, into a Chevak classroom. Marie Acemah, the founder and director of See Stories, said that her favorite part of this project was watching the interaction between the Elders and children. “When students are learning in a classroom, they know they are in school and act a certain way, not always paying full attention,” she said. “But when the Elders come in, there is an automatic respect, because that’s their culture. It turns into a conversation with someone they know and respect and may be quite possibly related to.”

Storytelling connects people and ideas; it is a method of conveying values, emotions, history, and ways of life. “It's a very ancient idea of sitting at the feet of the Elders and listening,” Acemah said, “but it is also very modern because you’re filming the interview. These kids are ingrained in Instagram reels and TikTok videos, so it’s sort of that union of Elders feeling heard, and kids being able to receive, because they can do something exciting. It’s merging cultural practices with modern technology. That’s the magic for me.”

Stepping into the classroom: The logistics

After the NSF grant came through in 2020, delays unfolded as the pandemic forced communities to shut down. Finally, in the fall of 2022, Acemah reached out to several Chevak teachers in the local school. “To really do a project like this in a meaningful and sustainable way, you have to have a teacher that is excited about that,” Acemah said.

Roger Reisman responded. Though kindergarten and fourth grade teachers were also interested, Reisman’s classroom of sixth graders were at the right age to start a project like this. “That is about the age where digital storytelling takes its roots,” she said. Editing can be challenging for younger classes. And this project was going to involve all the parts of making a video: researching the subject matter, figuring out what questions to ask, setting up sound, and editing. The students were even involved in location scouting, which was limited to the classroom and just outside the school, as it was winter at the time.

Before all that, the students had to learn how to use the equipment. “They held them all with care and caution,” Reisman said. “As teachers, we value a controlled environment, and the technology was just given to these kids to play with. I was really impressed by that. It really inspired them.”

To decide on what to film, the students split off into small groups, tasked with picking their favorite areas around Chevak like the playground, airport, tundra, fish camps, lakes, and radio station. Each student was going to make his or her own video, so they individually ranked the places to get as close to their top choice as possible. They then formulated questions that could spark conversation and practiced asking them with their peers. Students then set up their classroom for filming. “Within days, we had the production set. We had the lights, the booms, filmmakers, questions, and the Elders,” Reisman said. Then, on Friday, they ordered pizza and stayed late to edit their videos—all in a week’s time.

Having the kids tell stories about their lives, stories about Chevak, reinforced their sense of identity and place. “They really were trying to answer, ‘How did we get to where we are?” Reisman said.

The walrus in the classroom: Climate change and historical trauma

Discussing climate change is unavoidable in Alaska, where some areas are warming up to four times faster than the rest of the planet. “Ultimately, this project was very much climate related,” Acemah said. “As an outsider, I don’t know the depth of trauma living in a place for time immemorial and having it change so rapidly. That is something beyond my comprehension.” Fortunately, climate change entered the conversations naturally. “It didn’t have to be forced; it just happened,” Acemah said. When discussing the tundra, the Elders mentioned how much deeper they now need to dig to hit permafrost to store their food. When the Chevak River comes up, the Elders recall how much earlier it used to freeze up when they were young. They speak of moving Old Chevak to New Chevak, which lies on higher ground, to avoid flooding and storm surges.

Even beyond climate change, an apprehension looms beneath the surface. “There is so much tension between school and community everywhere in Alaska,” Acemah said. Asking the Elders to come into the classroom brings up historical trauma of former boarding schools that insisted on eroding Indigenous culture. “It’s a sensitive topic,” Acemah said. “That’s just at play, and inevitable from my perspective—based on the history.”

Acemah and her team are therefore sensitive about how Indigenous voices are documented. She said, “There are Elders who say, ‘I’m not going to be exploited,’ but if they are connecting their knowledge to the next generation, then the work feels meaningful to them.” So much about this project though is about providing a platform and tools for future storytelling. Acemah teaches students how to use equipment they already have access to like a smartphone and iPad, or how to set up a tripod with some rocks. The students also learn to follow certain film rules like the rules of thirds, and how to get good audio. “Storytelling doesn’t have to cost money,” Acemah said. “We teach them in ways that are sustainable—to use what they already have.”

By centering the videos around stories of meaningful places, the hope is to encourage Chevak youth to continue reaching out to their Elders. As Elder John Pingayak said in one of the videos, “You need to know the history of your people in order to advance.” To stop repeating errors of the past, children sit at the feet of their Elders. With the added benefit of the online atlas, now those stories can reach a larger audience and keep records for their children’s children.