Waking the Bear

Bear Ceremonialism

The importance of ceremonialism

Ceremonies are hugely important for sustaining the life, health and identity of communities. A ceremony gathers together a specific group of people and in doing so affirms their various relations to each other. In this way they make themselves visible as an identifiable community not an audience. Ceremonies become occasions for educating the community through songs and narratives. They strengthen community identity by reinforcing their beliefs about their origins and the origins of the world about them. Through ceremonies, the community acknowledges its shared responsibility for each other and for the world they share. Often songs and narratives are complemented by humorous, clowning sketches which emerge from the real life experiences of the community, and also the experience of community solidarity. Altogether the elements of a ceremony provide an education in worldview and community values. Communities whose ceremonies have been repressed or lost have proven to be very vulnerable to serious social harms.

Some of the most widespread types of ceremonies are World Renewal Ceremonies, like the Shalako Ceremony of the Zuni Indians of the American southwest, which occurs at the beginning of winter, when the Sacred Beings return to renew the people and the earth. Watanabe has defined another type of ceremony which he calls “Sending-off” Ceremonies, which involves animals ranging from Bear through Caribou to Marmot and from Herring through Salmon to Whales. All, in his view, share a common structure based on three mythological events: “1) the human host guiding the spirit guest to his home; 2) a welcoming party at the house to express gratitude to the spirit guest for the meat it has brought; and 3) sending off the guest so that it may begin the return journey.”1 According to Watanabe these sending-home ceremonies are the dominant type of animal ceremony among northern hunter-gatherers because they support two deep beliefs among northern hunter-gathers: “first, that any failure to perform the rituals will be reported by the game captured or killed to its fellows so as to offend the spirits, and they will not return, and, second, that the main purpose in observing this type of ceremony is to secure the reappearance of the game animals in the next seasons.” Watanabe also observes that the First Salmon Ceremony2, and indeed most such first harvest ceremonies, are closely related to Sending-Off ceremonies. Bear ceremonies in many ways resemble sending-home ceremonies.

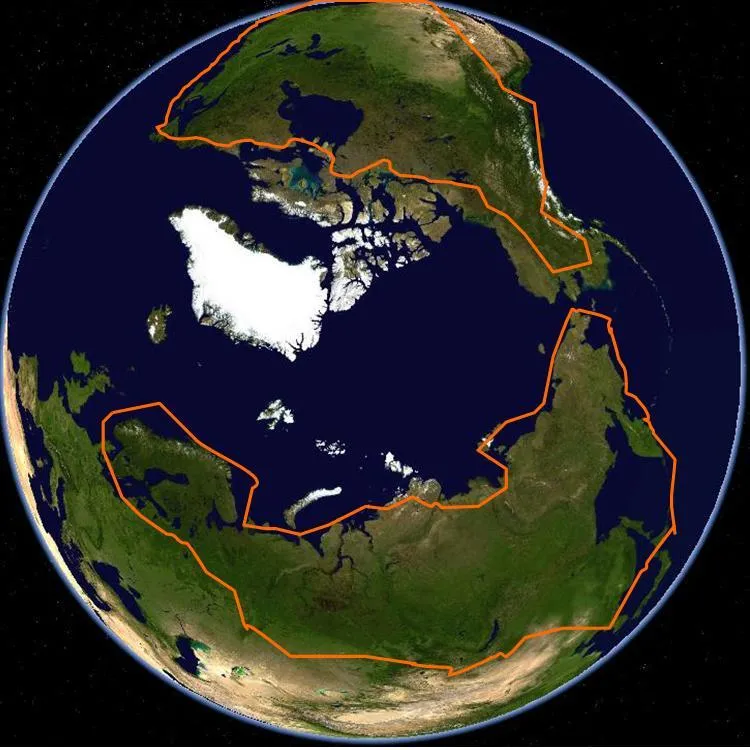

Bear ceremonialism, a circumpolar phenomenon

Bears are not the only animals who are so honored with ceremony. Many animals are thought of as other-than-human persons; they are understood to be spirits clothed in a certain body. After death, the spirit is thought to return to its place of origin. If the spirit has been treated well by the human community, perhaps in such a Sending-Home Ceremony, it will take on a new body and return to this world. But bears are unique among other-than-human persons in being so honored throughout the circumpolar north, from North America across Eurasia to the Sami of Scandinavia. Festival traditions featuring bears especially in winter are also popular across Europe though their relationship to Eurasian indigenous traditions is not clear, which is why Europe is not included on the accompanying map. The map outlines the vast area from which we have either archaeological remains, ethnographic descriptions or living practices of Bear Ceremonialism. Despite regional differences, similarities between bear ceremonial traditions in Eurasia and North America suggest that such traditions are very old and were probably brought to North America as people dispersed from Eurasia.

Loss, transformation and revival

Among some peoples, many bear ceremonial traditions have been lost. If not oral history, then only archaeology remains. Among others they are still quite active. What remains among most communities, certainly in Eurasia, are isolated elements of what was once a larger ceremonial complex. From time to time, sponsors have called for filming reenactments of Bear Ceremonies, but these do not lead to the renewal of tradition, which requires concerted community effort. The example of the Khanty and Mansi in western Siberia is instructive.

Among the Siberian Mansi and Khanty, during the years of Soviet power, the Bear Festival was under ideological prohibition, both because of its religious nature and its association with cultural primitivism. In the post war years, the Bear Ceremonial tradition was kept alive in secret; but irregular performance, age and oppression took their toll on tradition bearers. The breakthrough came in the second half of the 1980s, when the official status of traditional cultures changed. They began to be called “unique,” “original,” and received support from official authorities. In western Siberia, the renewal of interest is said to have started around 1986 by the Mansi writer Yuvan Shestalov. In 1988, carriers of both eastern and northern Khanty folk traditions were gathered in Khanty-Mansiysk in the new Torum Maa Ethnographic Open-Air Museum. Performers were brought there from throughout the okrug to celebrate the bear festival in regional variants. Brief video recordings are available here.

By the mid-1990s, ethnographic summer camps appeared for Khanty and Mansi village and city children where traditions were renewed. Bear festivals have been held among the Mansi approximately every five years or so from the mid-1990s up to the present, although the last Mansi Bear Song singer passed away ten years ago. They have been documented and directed by the Mansi folklore scholar, Svetlana Popova. Dr. Popova is directing workshops and organizing Bear Festivals throughout the northern Mansi region. More recently, through the Okrug House of Folk Art, the “Okrug school of bear games” was created. The Northern Khanty director, Timofei Moldanov, has developed special procedures for the transfer of traditional knowledge to children who do not speak or have a poor knowledge of the Northern Khanty language. Classes are held in a specially equipped room, in which, according to all the canons of the Northern Khanty religious beliefs, the Bear's head is placed. In the classroom, an artificially communicative language situation is created where the teacher speaks only the Khanty language. See a Russian television news video presenting the work of this school on YouTube here. A video broadcast of the lessons of the Bear Games school is being carried out through a Russian online social network. In addition, Timofei Moldanov maintains an online dictionary.

Some common features of bear ceremonialism

Every community brings its own needs to a ceremony. Some elements of ritual practice feature prominently in many, though not all bear ceremonial traditions. While most attention is focused on the “bear feast” or “bear ceremony” because it is highly visible and complex, bear ceremonialism involves many elements, some almost unnoticeable.

Black3 , summarizing Vasil'ev4 and Paproth5, identifies the following as "features that appear universally" in bear ceremonialism:

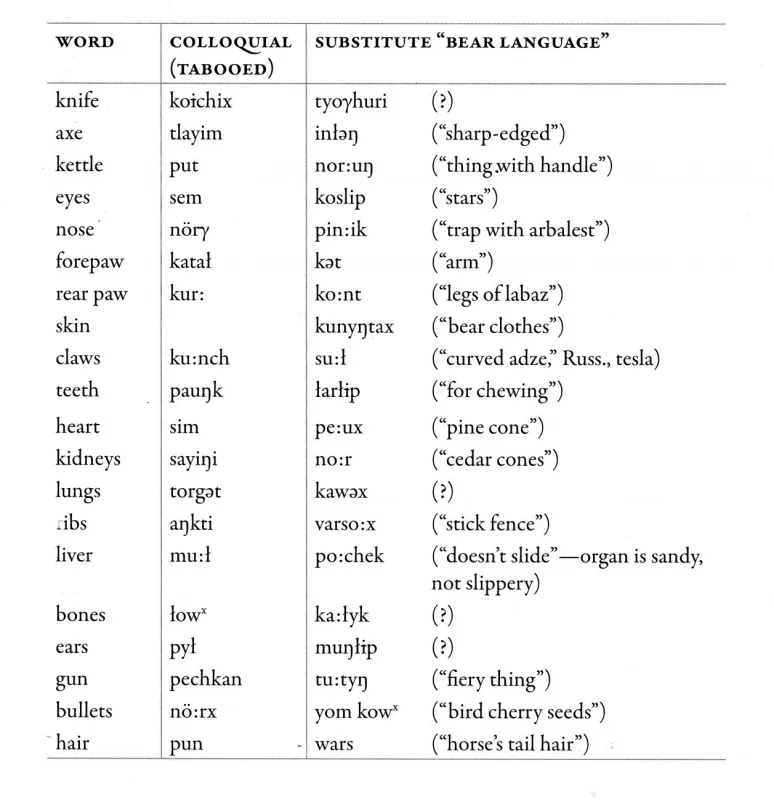

- special language for referring to Bear;

- ritualized hunting, skinning and butchering practices;

- addressing the bear ceremoniously prior to and after killing it, as well as at the feasts;

- partial or total exclusion of women in all matters concerning bears;

- ceremonial treatment of the slain bear with special treatment for selected body parts, especially eyes, nose, and genitalia;

- central ritual significance accorded the head (skull);

- ritual preparation of bear meat;

- the ritual preservation of the head, skull, bones, skin.

She also identifies a complex of widely-shared beliefs, such as the

- association of bears with power,

- transformation of bear to human and human to bear,

- "association of bear with the earth, often linked to metal, [and with] a burrow and hence substitution for bear and association with the bear of other burrowing animals."(1998:346)

Black’s list does not address the fact that there are two principal types of bear ceremonialism: the very widespread type that includes a hunt, and the much more localized Asian North Pacific type, most closely associated historically with the Ainu of Sakhalin and Hokkaido, that involves the death of a bear cub raised in the village. Moreover the claim of a “universal” listing misses the point that each part of the interaction with the bear has specific traditions that may vary from region to region.

Bear hunting traditions

A number of traditions are associated with bear hunting, often whether or not the hunt is meant to end in a bear ceremony of some kind. Most common are:

- Using a special language to refer to the bear and to the hunt, since the bear understands human language

- Having a specific customary time of hunting, during hibernation or when the bear is awake

- Ritually addressing the bear, apologizing for killing or transferring guilt to another group

- Special customs for skinning a bear and treatment of specific parts of the bear

- Avoiding breaking long bones.

Less common are:

- Leaving the bear in the forest overnight while gathering a group of men to come and retrieve it the next day

- Beating or skiing across the bear’s skin or across the trail used to bring the bear home

- Disguising various acts of skinning by describing them as natural acts of other creatures

- Having a special physical sign, such as placing a branch above the doorway, to wordlessly signal a successful hunt

- Avoidance of all boasting or insulting talk that demeans the bear

- Having a specific customary means of welcoming the bear to the village

- Marking the site of the bear’s death.

Bear festival/bear feast traditions

The most common of these are:

- Maintaining the use of “bear language” throughout the feasting

- Greeting the bear when it is brought to the village

- If the bear is brought to a village or settlement, almost invariably, the bear is treated as a guest of honor, and offered food, tobacco and drink. Among some peoples, the bear is entertained with songs and dances and even comic skits.

- Special attention is given to the head which may or may not have been skinned or cooked, and may or may not remain attached to rest of bear’s pelt

- Focus on the bear’s head involves its customary placement and ornamentation, doing homage to it, and special handling if involved in the feasting.

- For many peoples, this ceremony in an “eat-all” feast in which every part of the bear must be consumed.

- There are gender restrictions on the preparation and distribution of the bear meat.

Among some communities, gender restrictions are so severe that men only may touch or eat of the bear, so that among some peoples any commemoration of the bear takes place in the forest among the male hunters.

Less common

- The head is cooked separately

- The mandible is separated from skull

- Imitating raven or crow calls while eating

- Lips and nose cut out in a continuous ring and worn briefly by hunter to acquire the bear’s power of smell

- Swallowing of eyes whole to acquire bear’s vision power

Traditions after the festival

The most widespread traditions after the ceremony are associated with the disposition of the bear’s remains. Most common are

- Special treatment for the skull, sometimes along with the long bones of the forelegs, especially hanging on a tree or a high place.

- The disposition of all the other bones in culturally-specified place. Sometimes the bones are laid out on a platform, buried or deposited in still water.

- Preservation of certain parts as tokens of power or for healing, including claws, canine teeth, gall, penis bone, paws.

Less common are

- Public procession to place of deposition

- Preserving unskinned bear’s head from festival.

- Burial of all bones in anatomical order

- Wrestling, which simulates the hunter wrestling with the bear as other-than-human person

References

1 Watanabe, Hitoshi. "The animal cult of northern hunter-gatherers: Patterns and their ecological implications." Circumpolar religion and ecology: An anthropology of the north (1994):p. 55.

2 Gunther, Erna. "An analysis of the first salmon ceremony." American Anthropologist 28, no. 4 (1926): 605-617.

3 Black, L.T., 1998. Bear in human imagination and in ritual. Ursus, pp.343-347.

4 Vasil'iev, B,. A. 1948. Medvezhii prazdnik. Sovetskaia etnografiia. 4:78-104.

5 Paproth, H.J., 1976. Studien uber das Barenzeremoniell (Doctoral dissertation, Uppsala.). See also: Sokolova, Z.P., 2000. The bear cult. Archaeol. Ethnol. Anthropol. Eurasia, 2, p. 121-130.