Waking the Bear

Bear Festivals of West Siberia

West Siberian Indigenous Communities

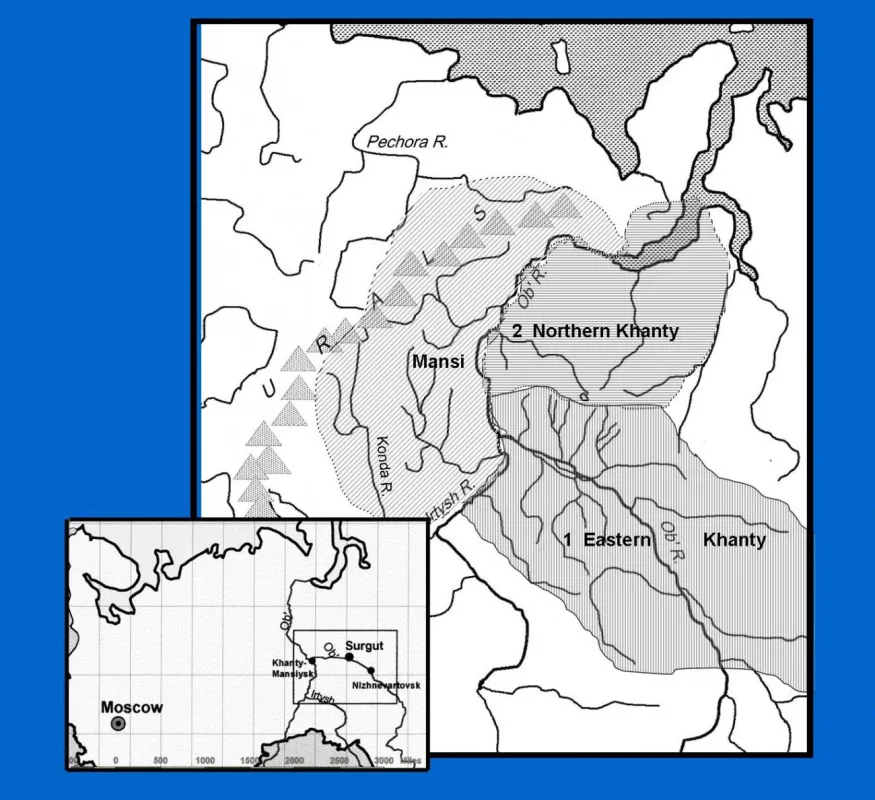

Western Siberia stretches from the forested zone of the Urals through the lowland taiga watershed by the Ob and Irtysh Rivers. Central Siberia reaches from the highlands along the Yenesei River eastward to the Lena River Basin. All of these rivers flow north into the Arctic Ocean from mountain ranges far to the south that separate this area from the steppe zone of central Asia.

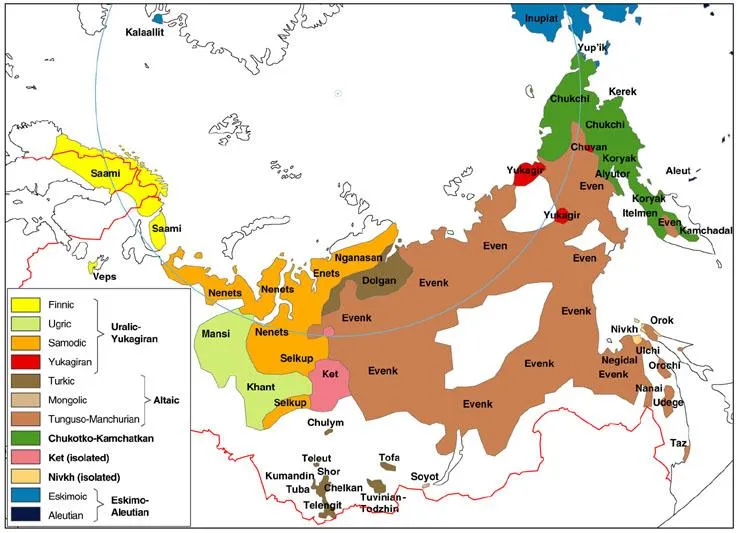

The oldest language family in this Urals area is the Finno-Ugrian, which has three branches.. Some groups of the Finnic-Permian branch of the Finno –Ugrian language family lived west of the Urals, and eventually settled as far away as the Estonia and Finland. Similarly another distinct language group, the Samoyedic branch, moved north and east eventually settling in the less forested and tundra areas along the Arctic Ocean shores from northern Siberia to west of the Urals, becoming today’s Nenets. The most numerous peoples in the Urals area were from the Ugrian branch of the Finno-Ugrian language family, the Mansi and the Khanty. Genetic research suggests that about 6,800 years ago ancestral populations of Western Siberians mixed with an ancient group most closely related to the modern-day Evenk, and that about 2000 years after that, the Mansi, Khanty, and Nenets began to separate.1 Mansi oral history supports a story of complex origins, telling that when they resettled in northwestern Siberia, they met and intermixed with another people already living there. The last major separation took place about 2000 years ago when the Magyars separated from the Khanty and Mansi living in the Ob’ River basin and moved westward, eventually settling in Hungary. After that, the largest tribes, the Khanty and Mansi, remained in the basin of the Ob River, and today are known collectively as Ob-Ugrians.

Far from being isolated, most of Russia’s 40 northern indigenous tribal peoples experienced migrations, displacements, and significant historical impacts from other populations. By the 10th century Russians in Novgorod were already trading steel war implements with Mansi who were then living on both sides of the northern Urals. The greatest impact came with the 13th century expansion of Mongol-Tatar armies across the steppe zone. They displaced the Yakuts northward, dividing widely scattered Evenk groups. Eventually the Mongol Khans exerted hegemony over the Russian princedoms that lasted until 1480. By the time of the Mongols, Ob-Ugrian Khanty and Mansi had settled throughout the basin of the Ob-Irtysh river system, whose tributaries drain the West Siberian Plain. For a long time the Ob-Ugrians had been middlemen, trading furs to the south through Mongol territory and across the northern Urals into Russia. The competition for fur territories was not without consequences. During the medieval period, they lived in fortified towns in a kind of feudal, socially-stratified society of chieftains or “princes , a warrior caste, and adjacent population. They paid a tax in furs, first to the Mongols—the fur tax is called iasak, which is a Turkic word—and then later to the Russians. After 1480, Russians forced the Mongol-Tatars to withdraw eastward toward and across the Urals. The Mongols divided their territories around the Urals and in Siberia into different khanates, over which they still exerted influence until a series of Russian campaigns in the 16th century displaced them. Nevertheless, the Tatars left their mark on Ob-Ugrian culture in gender roles, dress, and material culture.

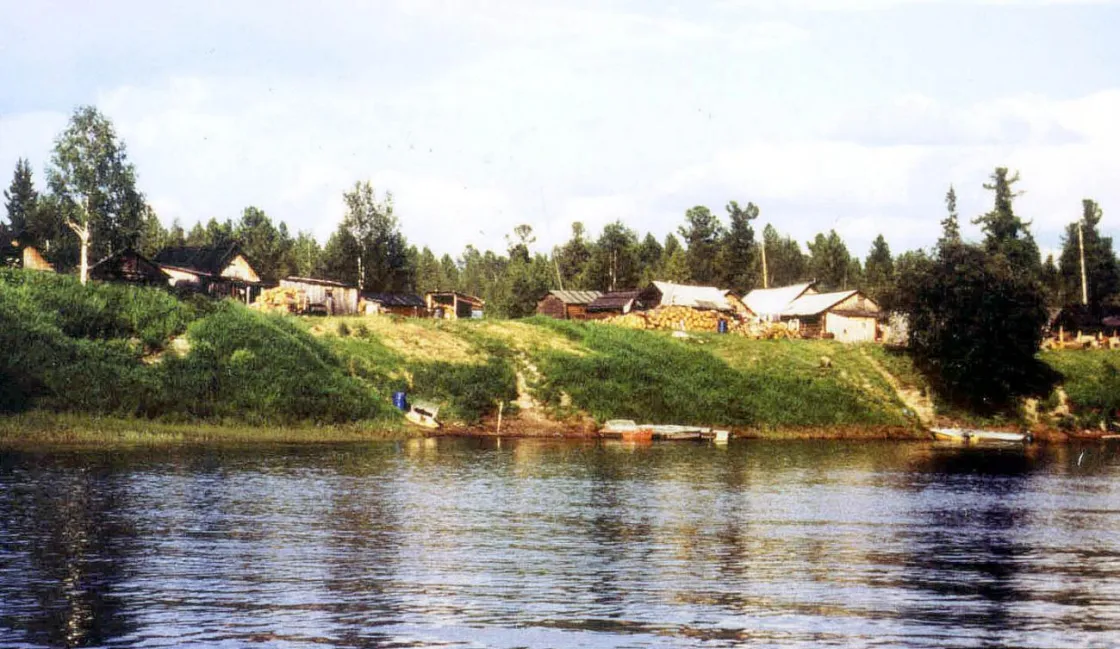

The establishment of Russian hegemony throughout Siberia saw the demise of the Ugrian princes and the dispersal of the population from fortified towns to widely-scattered settlements. Today Khanty and Mansi live principally by fishing, hunting, trapping and small-scale reindeer herding, with varying emphasis in local economies. Local group identity, usually based on river systems, was reinforced through use of the Russian volost (district) system to administer the collection of fur tribute. The eighteenth century also saw aggressive Christian proselytizing and direct attacks on indigenous religion. Limited reindeer domestication north of the Ob’ River grew to large-scale reindeer husbandry after 1700. Southern Mansi, living along the Pelym and Konda Rivers, and Southern Khanty groups, living near Tobolsk, were all assimilated by the early 20th century. The coming of Soviet power significantly reshaped indigenous economy by industrializing traditional subsistence harvest activities, introducing wages and currency, shifting the sense of property, and later introducing resettlement campaigns. The suppression of indigenous religious practices, the introduction of compulsory education, and acculturation campaigns that targeted a number of customary practices all substantially impacted indigenous culture. In the late Soviet and contemporary periods, state exploitation of oil and gas in Ob-Ugrian lands became the principal source of Russia’s wealth, but it has had devastating consequences for Western Siberia’s indigenous peoples. 2

Ob-Ugrian Bear Festival as Identity Symbol

It is probable that the Ob-Ugrian bear ceremony, as we know it today for the Northern Mansi, Northern Khanty and Eastern Khanty of Siberia, played a prominent role throughout this history of dispersal, transformation, aggression and repression. Early in the current era a style of bronze casting emerged in the Perm region which featured bears prominently among other animal figures, and may signal an important turning point in the historical development of the Ob-Ugrian Bear Ceremony. Among the Mansi and Northern Khanty, Chernetsov distinguished between two types of festivals involving the bear—the sporadic and the periodic.3 The ‘sporadic’ bear festival was performed after a bear was hunted and killed. For the Northern Khanty and Mansi, the final night was designated the “Holy Night” and patron spirits came to dance before the bear. Some of the animal dances Chernetsov interpreted as having a totemic character. The ‘periodic’ bear festival was held seasonally, in association with the summer and winter equinoxes, in specially designated villages to which the population of clan relatives was obliged to come and participate, bringing with them the images of their clan ancestors and participate. These ceremonies, according to Chernetsov were related to the complex phratrial-clan organization of the Mansi. These occasions were longer and more complex than the sporadic bear festival, because additional features having to do with social relations were added. This type of celebration does not seem to have been part of the Eastern Khanty tradition. Chernetsov hypothesized that the sporadic festival represented a devolution from the periodic festival, but the reverse is also not unlikely: that the simpler, post-hunt bear festival evolved, with the addition of clan-related elements, to become a key identity symbol that functioned to integrate various local Ob-Ugrian villages and families. 4, 5

Main Features of Ob-Ugrian Bear Festivals

While Ob-Ugrian bear ceremonialism incorporates the whole activity from the hunt, to the communal celebration, to the disposition of the bones, we attend here only to the basic structure of Ob-Ugrian Bear communal celebration, which focuses on some generally shared features, below. The Ob'-Ugrian bear ceremony is not a "sacred" ceremony or religious ritual, in the sense of being closed to strangers and the uninitiated. It is a public community celebration, hosted by members of the community, conducted according to a general formal pattern elicited from community memory, to which non-community members can be invited, and with permission it can be photographed. Although not a religious ritual, it nevertheless demands respect from all who attend.

- DEFINITION OF PERFORMATIVE TIME AND SPACE. Traditionally, the length of the celebration is determined by the age/gender of the bear taken -- 3 days if a cub, 4 days if a female, 5 days if a male. Within the frame of the festival proper, the festival "night" is defined not by the diurnal cycle but by performative elements, such as special songs to wake the bear and put it to sleep. The festival takes place in the home of the hunter, though it may also be hosted in another house which is larger. Northern Mansi communities had a tradition of building a special, much larger house for community celebrations. The Bear, richly clothed and adorned according to its gender, is seated in the place of honor on the sleeping platform or raised table opposite the door or in the special corner reserved for icons. Among Eastern Khanty a special house is built for the bear. The audience is gender-segregated and lines the walls, defining the performative space in front of the bear.

- SONGS. The festival proper opens with songs, the first of which retells the story of how the bear came to be lowered down from the sky by his Heavenly Father, of his travels and life on earth and how he came eventually to be in this place where he is being honored. A number of songs follow and make up the most important part of the ceremony, often quite long. There are regional variations in singing, but singers disguise themselves with special costumes and cover their hands, and use a staff to keep rhythm. Special songs for waking the bear and putting him to sleep each ”night” are accompanied by the ringing or other jingling sound produced by a small bell or other means attached to a string fixed near the bear and pulled rhythmically by the singer. At the end of each ceremonial “night,” the bear is put to sleep with a special song and its head entirely covered by a scarf.

- DANCES. Both men and women dance, though separately. Dances are roughly mimetic. Men dance imitating the gait of the bear or a hunter by stepping heavily forward in a crouched position. Women imitate gathering birdcherry or other activities, and must dance before the bear with the heads entirely obscured under a large shawl draped over their heads and supported by outstretched arms. Men’s hands are covered by gloves, women’s by the ends of their shawls.

- SKITS. Clowning is a required and important part of the bear festival and accounts for the characterization of the event in its Russian name, as “bear games”. Certain skits are well-known and seem to be frequently performed throughout the entire Ob-Ugrian area and persist even to this day. Many of the skits involve courtship, marriage or sexual behavior, feature erotic humor, and often use a stick or pole as a symbolic phallus. Clowning is done in a special costume that consists of a long, brown hooded felt garment, often used as an inner coat under the colorful thigh-length parka (malitsa). Like singers, actors wear masks made of birch, a portion of which has been cut out to form a large nose, and usually disguise their voices by speaking in falsetto.

- DIVINATION. Various forms of divination are employed to gain hunting luck, to determine who will get the next bear, host the next festival and how soon (which, of course, is also a matter of hunting luck).

- FEASTING. Elaborate feasting with a plentiful table, even to the point of emptying the larder, is essential. Feasting takes place while the bear "sleeps." In customary Ob'-Ugrian fashion, men and women sit separately. In ethnographic literature, provisioning guests was of such importance that that a host might call on family and friends to supply food and drink to make up his own deficit. And we should not forget that the bear is provided with its own portions of bread, berries, meat, candy, vodka, and tobacco, so as to share in the feasting.

These elements are the core of Ob-Ugrian Bear Festivals, but the peoples of western Siberia have local variations of the Bear Ceremony, for example, requiring an animal sacrifice before or during the ceremony. Mansi scholar Svetlana Popova sees in the Bear Festival elements of the traditional funeral. “Every day, in the morning and in the evening, throughout the whole holiday, hot food is put on the table in front of the head: meat, fish, and everything that stood before and is already cold is passed on to the common table. Thus, allegedly, the beast takes part in the universal meal. But if one looks deep into the tradition, there is an analogy with the rituals of the funeral ceremony: Mansi ‘invite’ the deceased relative to the daily meal twice a day - in the morning at sunrise and in the evening at sunset, this time of day correlates with the transition state.” 6 The sporadic bear festival as practiced today in western Siberia, illustrated with video, photos and texts, is described in the following pages.

Read on to learn about the regional variants of Ob-Ugrian Bear Festivals including film and photos that illustrate how the bear festival is practiced today by different peoples in western Siberia.

Northern Mansi

Apart from those Mansi who live in the regional capital, Khanty-Mansiysk, today most of the 9000 Mansi live in the northwest part of Khanty-Mansi Okrug-Iugra, along the Northern Sosva, Lyapin and upper Lozva rivers. It was not always so. The northern Mansi group emerged relatively recently, when a Khanty population, already resident in the Sosva region, received emigrant Mansi groups, who had been driven out of their lands on the western slopes of the Urals. Russians, pushing back the Tatars, had expanded into the Perm region, hastening the northward expansion of some of the Komi population then living in the Perm region, putting pressure on Mansi living north of Perm. When the Mansi Pelym principality, a Tatar ally, was liquidated, people from Pelym, Lozva and Konda also moved northwards and took part in the formation of the northern Mansi. The northward emigration of Mansi from these territories to Northern Sosva and Lyapin Rivers continued into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.1 Today, these Northern Mansi constitute the vast majority of the Mansi population, with some remnant populations in the south. Over the course of the last four centuries, all have been subject to enormous acculturative pressures. Today many northern Mansi live in sizeable villages, while some maintain seasonal or year-round extended family settlements like Khanty.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the rise of nationalism in Hungary and Finland led scholars in those countries to explore the remote Finno-Ugric peoples to whom their languages were related. Important work among the Mansi was done by the Hungarian scholars, Antal Reguly and Bernat Munkácsi who traveled to Siberia in the nineteenth century. In Finland, the Finno-Ugrian Society was founded in 1883, by which time August Ahlquist had already made three trips to Siberia and completed very serious work on the Mansi; he was followed by Artur Kannisto who, among his other work, collected Bear Festival songs from Konda Mansi and from the Northern Mansi. Today the work of revival and scholarship is carried on by indigenous Mansi scholars. The late Yevdokia Ivanovna Rombandeeva, a Mansi folklorist and linguist, among many other accomplishments, translated into Russian and published Mansi Bear Festival songs transcribed by the Hungarian scholar, Bernat Munkácsi. 2 A contemporary Mansi scholar and NSF research team member, Svetlana Popova, made essential contributions to the description and video presented here. 3

Some of the similarities between the Northern Khanty and Northern Mansi Bear Festivals may be accounted for by the historical amalgamation of a resident northern Khanty population with Mansi groups coming from the west and south. Chernetsov distinguished between sporadic bear festivals, held after the killing of the bear, and much larger, social gatherings of which the bear festival was a part which were held periodically at places like Vezhakory. These periodic festivals, associated with the winter and summer solstice, were known as the “big dances” or “great dances,” and functioned to renew the bonds between the groups and affirm the social order, of which the bear was the symbol. In every village, there was a main house for celebration, and historically the preservation of images of spirits and offerings. In Lombovozh it was the house of the Sheskin princes, but when it was destroyed, a new one was built in its place. The Lombovozh bear festival highlighted in the accompanying video celebrated the inauguration of the new big house. Today the Mansi only celebrate the sporadic variant, the last periodic festival having been celebrated in 1977. Both versions feature the Sacred Night, but different deities are present. 4

The Northern Mansi Bear Festival

According to S. Popova, in every Mansi village, ”The structure of the sporadic bear festival among Mansi is based on the following elements: locating the den; extraction, delivery and meeting of the bear in the settlement; preparatory actions; cleansing and fortune telling; the festival itself, accompanied by chants, dances and dramatic performances; the rite of animal sacrifice; sacred night with the introduction of the spirit patron saints of the nay-ōtyr’ov, literally, ‘Heroines- bogatyrs’, in an anthropomorphic image and ancestors of the clans in the hypostasis of an animal; "animal and bird" dances; the destruction of the [bear’s] table; the removal of the bear head, the farewell and the commemoration.” 5

The Northern Mansi Bear Festival is clearly divided into two parts, unequal in duration and significance. The first is a section of songs, skits, and both men’s and women’s dancing, accompanied by music. Here there are several important differences with the Northern Khanty. Perhaps the most important of these is that at present, as among the Yugan Khanty, death has taken the last of the elder singers of Bear songs; this last singer is shown in the video below inviting the deities to the Sacred Night. The texts of such songs have been recorded by the Finnish scholar Artur Kannisto6 and made available in both Mansi and Russian, so their general themes and structure known.7 Among the most important of these songs is the song that tells the Mansi story of how the bear was lowered from the Skyworld into this world, a version of which you can read in English for the first time in this PDF, SONG OF LOWERING THE BEAR FROM THE SKY. The comic skits are also well-documented, including their texts, and have been published recently.8 While both Northern Khanty and Northern Mansi will offer an animal as a blood sacrifice, the Northern Khanty do so (in this case a reindeer) before the actual festival begins and away from the festival house. The Mansi also sacrifice an animal (at Lombovozh a calf) though not outside but inside the house in the presence of the bear. In at least one Northern Mansi Bear Festival, that at Kimkyasui in 1994, a single woman from Sosva danced what was known as the ‘bear dance’, which was unique and shown in the video below. In the general knowledge, only this woman knew this dance and its significance, and since she has passed away, it has never been repeated. After this dance, it is said, women should no longer dance but only be spectators.

Like the Northern Khanty Bear Festival, the Northern Mansi Bear Festival concludes with the Sacred Night, when deities make their appearance. Each features some common Ob-Ugrian personages, such as the Crane who tries to destroy the bear’s place, and Kaltashch, the great mother, but in both cases some of the deities are local and very specific to each group. The Mansi Sacred Night Performance is distinguished by its clear associations with the Ural Mountains and with times of hostilities. Specific to the Mansi tradition of the Sacred Night, for instance, is the Dance of the Seven Bogatyrs (Warriors), which comes in several parts. The story behind it begins with a hunter, who sees a boat coming from far off. As it approaches, he is terrified to see they are warriors, but they tell him not to be afraid and to accept them as his defenders and patrons, which he does. This set of dances clearly belongs to a period of hostilities, perhaps when the Mansi were allied with the Tatars against the Russians. Another unique figure is Payping Oika, “The protector of the settlement,” who is armed and searches the four corners of the performance space on the lookout for potential attacks. Hont Torum, the God of War, well-armed with clashing arrows, also appears. Tulang urne oyka, The Guardian of the Seven Finger Mountains (the Urals), is always depicted carrying two larch trees.

Finally, when the festival is over, the bear’s male guardians send the women out of the house so the bear can be discreetly carried away to the forest. When the men exit the house, however, they are showered with snow by the women, who cry “Why are you taking away my younger brother?”, and made to circle the house three times. When they are finally able to get away, the men are confronted by Raven, who makes a last try at stealing the bear’s soul before he too is defeated, and the bear successfully returns to the forest. The Mansi Bear Festival thus dramatizes their relationship to the forests and the Ural mountains.

References

1 Popova, S. 2018. Общая структура Праздника Медведя в Северном Манси. Unpublished ms.

2 Мункáчи, Б. [2012]. Медвежьи Эпические Песни Манси (Вогулов), том. III. Russian Translation, Rombandeeva, E. I. Khanty-Mansiysk.

3 Попова С. А., 2017.Медвежий праздник северной группы манси: языковое табу. Финно-угорский мир. № 3. pp. 102–112; 2015. Роль периодического медвежьего праздника Яныг Йикв в формировании социума северных манси Вестник угроведения №1 (20) 89-100; 2013. Этническая история и мифологическая картина мира манси. Ханты-Мансийск; 2011. Медвежий праздник на Северном Урале. Ханты-Мансийск/

4 Chernetsov, V.N., 1968. Periodicheskie obriady i tseremonnye u Obskikh Ugrov, sviazannye s medvedem [Periodic rituals and ceremonies of the Ob-Ugrians, connected with the bear]. In Congressus Secundus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarium. Pars II Acta Etnologica (Vol. 10, p. 16). Societas Fenno-Ugrica Helsinki.

5 Popova, S. 2018. Общая структура Праздника Медведя в Северном Манси. Unpublished ms.

6 Каннисто, А [2016]. Мансийские песни о медведе в записи Артура Каннисто. Перевод с немецкого языка Н. В. Лукиной. Томск.

7 Мункáчи, Б. [2012]. Медвежьи Эпические Песни Манси (Вогулов), том. III. Russian Translation, Rombandeeva, E. I. Khanty-Mansiysk

8 Каннисто, А., Лиимола [2016] Драматические представления на медвежьем празднике манси. Переиод с немецкого языка и публикация Н. В. Лукиной Ханты-Мансийскю

Northern Khanty

Northern Khanty, speaking the northernmost dialect of the Khanty language, live north of the confluence of the Ob’ and Irtysh Rivers. They are by far more numerous and widespread than the eastern Khanty. Northern Khanty live mostly in the basin of the Kazym River and other tributaries of the right bank of the lower Ob’, all the way to its mouth above Salekhard. Today some live in the okrug capital Khanty-Mansiysk, others live in a few village settlements, but most continue to live in separate extended family settlements, where they subsist on fishing and reindeer herding.

Three key moments, among others, today stand out in the cultural life of the northern Khanty. First, the Kazym River Khanty resisted Soviet policies in what became known the “Kazym Uprising”. Kazym was a new Soviet village set up as a “cultural base” from which to disseminate and enforce a number of Soviet policies including compulsory education, collectivization and atheism. The first led to the forcible removal of children to boarding schools, the second to the confiscation of privately owned reindeer herds and collectivized fishing in sacred Lake Num-To, and the last to the arrest and execution of shamans. Such policies led to conflicts, for which a permanent negotiated solution could not be found. In 1933 Soviet regional officials came to a Khanty camp where they captured and beat the rebellious Khanty; that evening a Khanty shaman ordered those Soviets ritually killed by strangulation. Some time later, after one brief skirmish, 88 Khanty and Forest Nenets were arrested, more than half of whom were ultimately imprisoned. One consequence of this event is that the hunting of bears and celebration of the Bear Festival was banned by the Soviets. Today members of those same Khanty families are leading the Northern Khanty Bear Festival revival. 1 , 2

Second, the Soviet Union determined that the Kazym (northern) dialect would become the official dialect of the Khanty, and it is promoted to this day in publications and performances. This circumstance has meant that Northern Khanty also reap many benefits from the politics of culture. Today most of the Khanty cultural elite are northern Khanty, and they have played an important role in the revival of the Bear Festival.

Third, the Kazym River as a tributary flowing westward eventually enters Ob’ River floodplain not far from where the Northern Sosva River, flowing eastward out of Mansi country, enters the opposite side of the Ob’ floodplain. This made for regular communication between the Northern Mansi and Northern Khanty, and several important sites emerged, such as Vezhakory, for shared meetings and periodic Bear Festival celebrations, witnessed in the 1930s by the Soviet ethnographer V. N. Chernetzov3, which probably accounts for the similarity between the two variants of the Bear Ceremony.

Northern Khanty Bear Festival

The northern Khanty Bear Festival, sometimes simply called the Kazym Bear Festival, has been made the subject of intensive study. Timofei Moldanov, who wrote his dissertation on the subject, has led its revival and renewal, and specialized in the worldview and types of songs the Bear Festival discloses.4 Tatiana Moldanova has specialized in northern Khanty ethnology and provided with annotations the “Song of Pelym Torum,” one of the most important songs performed during the festival, which can be read here. She has also written a book-length commentary on the song.5 Both indigenous scholars are members of the NSF research team and have made essential contributions to the description and video presented below on this page.

According to Tatiana Moldanova, the northern Khanty Bear Festival is distinguished by the structuring of specific sets of song materials. Within these sets of songs, some are required and some are optional. Every day of the festival, including the first, begins with the song of waking the bear. After this, each day come three, five, or seven Bear Songs; of these, the required ones are those that describe the bear's heavenly origin and the one which describes his earthly origin, the song of Pelym Torum. Bear Songs also include some geographic songs describing the bear’s wanderings, as well as the mandatory Bear Song on the last day that directs the bear’s souls (four for female, five for male) towards the Skyworld. A second set of song materials are devoted to the mish, spirit guardians of lakes and other places who bring good luck in hunting and fishing. A third set of song materials are about the mengkv, or forest spirits, who are guarantors of correct behavior in nature. Both mish and mengkv songs can involve the fourth genre, hlungalthtup, sometimes called skits or scenes, performed by characters in birchbark masks. Their presence is signaled early on by the “Song of the Arrival of the People from Pechora River.” Personages behind the mask are permitted everything, in good humor, including misbehavior and eroticism, but they are often chastised for it, as in the skit where the mengk chastises the disrespectful boatmen on the river. Men’s and Women’s dancing plays a very prominent part. The several days of songs, dances and skits are formally closed by the sweeping away of soot (evil) by scarves held in the hands of a sister who, with her brother, have come from the headwaters of the Irtysh for this purpose. Then the so-called Holy Night opens with the Song of Pelym Torum, which tells of the earthly origin of the bear. Then the great spirits and patrons of families come before the bear with songs and dances. These include Kazym Imi, the patroness of the Kazym people, and many other deities. If the deity is connected with the upper world, he wears a white kaftan and a red fox fur cap. If he is connected with the underworld, he dresses in dark clothes, and wears a black fox cap. Then the great goddess Kaltashch, accompanied by the clacking of arrowheads to drive away evil, comes to tell how she ordered everything on earth, and in the second part, turns to the women and instructs them on how to behave before and after childbirth. The Bear Festival ends with the arrival of animals who try to steal the souls of the bear, like the Crane, whose nest was destroyed by the bear, but failing that he destroys the bear’s house. The high god Torum comes with his seven sons to honor the bear. Thus the whole Khanty universe is made present to those who attend the Bear Festival.

The Song of Pelym Torum

“The Song of Pelym Torum” is one of the most important songs of the Bear Songs genre (Kh., “kайёяӈ ар”, literally “howling song”). It is part of the shared heritage of the Northern Khanty and the Mansi. Pulum Torum (as his name is pronounced in the song) is one of the sons of Numi-Torum, the highest deity, who divided the earth’s territory among his seven children. Pulum Torum is the deity responsible for the territory around the Pelym River. According to Mansi traditions, at the upper part of Pelym River, which flows out of the Ural Mountains, is the base of the opening that connects the Earth to the Sky World above. Several moments in the text of the song suggest that the cub, sometimes affectionately referred to as a “little chick,” is a child who assumes the image of a tundra beast, that is, a bear. Both the cub and Pulum Torum can also appear as men. The Song is extremely important because it tells how the bear with Pulum Torum established the precedents for conducting the bear festival,and for hunting, fishing and traveling.

Further information can be found in Молданова, Татьяна, 2010. Пелымский Торум – устроитель медвежьих игрищ. Ханты-Мансийск: Полиграфист, 2010.

Here is the full, trilingual text of the song in Khanty, Russian, and English, as performed on 3 March, 2015, as sung by A. A. Yernikhov at a Bear Festival in Kazym, Khanty-Mansi AO-Yugra, Russia.

You can listen to the song by playing the .mp3 files linked below.

Song of Pelym Torum MP3 Part 1

Song of Pelym Torum MP3 Part 2

References

1 Чернецов, В. Н. 2001. Медвежий праздник у обских угров. Перевод с немецкого и публикация Н. В.Лукиной Томск: Изд-во ТГУ.

2 Balzer, Marjorie.1999. The Tenacity of Ethnicity: A Siberian Saga in Global Perspective. Princeton U P. Ch. 4

Леэте, Арт. 2004. Казымская Война: восстание хантов и лесных ненцев против советской власти. Pyltsamaa.

4 Moldanov, T. A. 2002. Картина мира в медвежьих игрищах северных хантов XIX –XX вв.: Дис. …канд. ист. наук. Tomsk; Moldanov, T. A. and Sidorova, E.V. 2010. Хантыйские медвежьи игрища: танцы, песни. Khanty-Mansiysk. See also: Schmidt, É., 1989. Bear cult and mythology of the Northern Ob-Ugrians. Uralic Mythology and Folklore. Ethnologica Uralica, 1.

5 Moldanova, T. A. 2010. Пелымский Торум – устроитель медвежьих игрищ. Khanty-Mansiysk; Moldanova, T. A. and T. A. Moldanov. 2000. Боги земли Казымской. Тomsk.

The Eastern Khanty

Nearly 30,000 persons self-identified as Khanty in the 2010 census making them one of the most numerous minority indigenous peoples of the north, as the Russian government categorizes native peoples. Khanty groups are distinguished by their region of residence and by dialectical differences, which are so great as to amount to almost separate languages.

The eastern Khanty live mostly in Surgut and Nizhnevartovsk districts of Khanty-Mansi AO-Iugra with a few in the Nefteyugansk district and altogether number no more than 5000. Few of them are urbanized, especially in Surgut and Nizhnevartovsk districts, choosing instead to live in their widely scattered extended family settlements along the banks of the major tributaries of the great Ob: on the north side, the Pim, Lyamin, Tromegan and Agan Rivers, and on the south side, the Salym, Bolshoi and Malyi Yugan Rivers. A small number live on the upper reaches of the Vakh River. Some few others along the upper Demyanka and Vas-Yugan Rivers in Tyumen Oblast. Their traditional family hunting territories are protected by family gods who are considered offspring of lineage-founding deities. They believe that sacred power has been historically invested in both the landscape and the lineage. These gods are said to live in specific sacred places, and often have shrines marking these sites. The gods are worshiped through blood sacrifice (yir) of animals, especially reindeer, and through bloodless sacrifice (pory) of boiled meat.

Until the 1990s, most families lived a subsistence economy of fishing, hunting and trapping. There are significant differences, however. On the north side of the Ob, eastern Khanty, like their northern Khanty counterparts, also engage in small scale reindeer herding. Only on the south side of the middle Ob’ and along its easternmost tributaries, such as the Bolshoi Yugan River, does the pure fishing-hunting economy remain. You can learn more about the Yugan Khanty community at this external website. Ob-Ugrian social organization is based on extended families or patrilineages, with related lineages grouped into clans. Despite the efforts of Christian churches and the suppression of native religion under the Soviets, traditional belief and ritual still flourish. Prayer and sacrifice insured long life, tranquility, fertility, prosperity, and protection from and healing of disease and injury. The eastern Khanty are rapidly being overwhelmed by petroleum exploitation, which has polluted the land and rivers, making hunting and fishing difficult. It has commodified traditional family lands by making them leasable to petroleum companies, and the cash and luxury products made available this way have disrupted the traditional economy and had a negative effect on eastern Khanty traditions. By 2010 most of the elder generation who had survived World War II and carried forward both the subsistence economy and traditional beliefs and practices had passed away.1

Unique features of the the Eastern Khanty Bear Ceremony

Ob-Ugrians live in the middle world of a three zone cosmos, between an upper, sky world and an underworld. Each of these is further divided into seven levels. The high god, Numi Torum, is not to be approached directly but only through addressing one or more of his seven sons and seven daughters and their children. Because the patrons of the major tributary river systems are also lineage-founding deities, different clans claim traditional use rights to different river systems tributary to the Ob’.

As the Mansi consider the Bear one of the daughters of Numi-Torum, the Khanty consider the Bear one of his sons. The Bear is the patron of the Bolshoi Yugan River, where his major shrine is located; one of his other names is Yaoun Iki, Yugan Elder, and one of the prominent clans is the Bear Clan. The Yugan basin is heavily forested, and there are many bears. Bear festivals, known in eastern Khanty language as pupi kot (“bear’s house”) or pupi yek (“bear dances”) are not performed after the killing of every bear. The decision of whether to sponsor a bear festival falls to the hunter. Prior to the recent renewal of the Yugan tradition, the most recent Bear Ceremonies celebrated on the Bolshoi Yugan were in 1995 and before that in 1988, by two renowned singers. Both of them appear in this video clip below of the opening of the 1995 ceremony, and one sings a unique variant of the song of the “Coming of the Bear”. A trilingual—Khanty, Russian, English-- translation of that song is available here.

Song of the Coming of the Bear

Sung by N. P. Kuplandeyev, Larlomkiny, Bolshoi Yugan River, 1995, Photo credit Timofei Moldanov

By 2007, the Yugan Khanty, a community of more than 800 people, were without a tradition bearer who could even serve as a teacher. A grant from UNESCO's Moscow office made possible in 2010 the first performance of the Khanty Bear Ceremony in 15 years among the Yugan Khanty, by bringing to the Yugan community two eastern Khanty singers of Bear songs from the adjacent Tromegan River region. A second Bear Festival was performed according to local traditions in 2016, with invited Khanty guests from the Demyanka River where the tradition was hanging on by a thread. Elements from these two performances have been edited to produce the Eastern Khanty Bear Festival video on this page. Important contributions to this description and to translating eastern Khanty songs were made by NSF team member, Elena Surlomkina, a native speaker, and daughter of Petr Kurlomkin, one of the last Bear Festival singers among the Yugan Khanty.

The structure of the Eastern Khanty Bear Festival differs significantly from the Northern Khanty and Mansi Bear festival. The bear is brought in through the back window, which substitutes for smoke hole opening to heaven, which is no longer part of Siberian indigenous architecture. A special house for the bear is built on a platform with walls of wood strips, gridded 4x4 for a female bear, 5x5, for a male bear. A special counting stick is made in which notches are cut for each song, story or skit that is performed before the bear. The singers wear no special costume, hats or gloves, but put on women’s kaftans and shawls to disguise their identity. Singing predominates much more than skits or dancing, though both have their place. Singers do not sing in a group or link with their little fingers their swinging hands. Most noticeable is the absence of the “Sacred Night” and the visitation of local deities, so prominent in the Northern Khanty and Mansi, yet familiar personages like the Horned Owl, the Crane and the Raven, are present. Divination is also present, but more commonly in the form of table-raising or porridge divination, although divination by shooting the arrow into the wall was documented among the eastern Khanty on Agan River in the 1988 reconstruction filmed by Lennart Meri. On the Yugan, at the end of the festival, a path of white cloth is laid leading the bear out of the house, where it is placed on the snow facing southwards and the sun. Male guests are invited to a special feast of the bear’s cooked head and paws in the evening. The Eastern Khanty Bear festival seems a clear type of Sending-Home ceremony.

References

1Wiget, A. and O. Balalaeva, 2011. Khanty, People of the Taiga: Surviving the Twentieth Century. Fairbanks: U of Alaska P, 2011.